I think one of the best ways for me to utilize this forum would be as a sort of bulletin board. With my limited writing abilities, cutting and pasting of cogent articles, statements and images seems like a no-brainer. This will free me up to add the infrequent rant and occasional comment.

Before my father died, he made the statement " I'm sorry I fought for this country". This was a lifelong Republican's response to the Abu Ghraib revelations and general realization of the dullness of our commander in chief. He fought in the Pacific as a gunner on the large landing crafts called LST's. He recalled how scared the few Japanese prisoners were when brought aboard to be ferried to hospital ships, how they cowered knowing what was to become of them shortly, having been told by their commanders that we were barbarians and would torture them to the death. He told how they slowley would come to the realization that this was not going to take place as the medics would tend their wounds, seamen would light cigarettes for them, etc... He told how many would not have fought to the death, taken a large amount of ours with them in futility. He admitted that there were plenty of atrocities on the battlefield, but he never witnessed any behind the scenes. "We don't do stuff like that".

This just out today at Huffintonpost about info gathered casually.

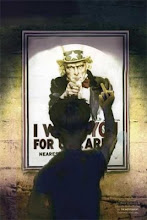

Image from: www.blognetnews.com/

An op-ad from Morris Davis, chief prosecutor for the military commissions at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, from 2005 to 2007, reinforces what used to be our standing in the eyes of the world.

____________________________________________________________________

Unforgivable Behavior, Inadmissible Evidence

Published:

The New York Times

TWENTY-SEVEN years ago, in the final days of the

After humiliating prisoners at Abu Ghraib by forcing them to strip naked and lie in a pile like a stack of firewood or simulating the drowning of detainees to persuade them to talk, we can no longer say we “don’t do stuff like that” — and we do not have to look far to see the damage. The disclosure last month of a manual for Canadian diplomats listing the

During the Persian Gulf war in 1991, the Iraqi armed forces surrendered by the tens of thousands because they believed Americans would treat them humanely. Our troops reached the outskirts of

Would it have been different if the perception of us as purveyors of torture and humiliation existed back then? Would tens of thousands of Iraqis have put down their weapons if they believed they were going to be humiliated, abused or tortured, or would they have fought? Had they chosen to fight, the war would have lasted longer and cost more and casualties would have skyrocketed. Our reputation in 1991 as the good guys paid dividends and supported our national interests. We must regain that reputation.

We can start by renouncing cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment of detainees and unreservedly committing to uphold the Detainee Treatment Act, which passed Congress in 2005 but was diluted by a presidential signing statement. We must also reaffirm our adherence to the United Nations Convention Against Torture, which the Senate ratified in 1990.

My policy as the chief prosecutor for the military commissions at Guantánamo was that evidence derived through waterboarding was off limits. That should still be our policy. To do otherwise is not only an affront to American justice, it will potentially put prosecutors at risk for using illegally obtained evidence.

Unfortunately, I was overruled on the question, and I resigned my position to call attention to the issue — efforts that were hampered by my being placed under a gag rule and ordered not to testify at a Senate hearing. While some high-level military and civilian officials have rightly expressed indignation on the issue, the current state can be described generally as indifference and inaction.

There are some bad men at

Morris Davis, an Air Force colonel, was the chief prosecutor for the military commissions at

No comments:

Post a Comment